You're doing leisure wrong

Escaping the hell of "total work" & why Sabbath rest is not optional

[In which I write way too many words and overuse quotes and italics. And in which I explore what it means to live a fully human experience, so maybe it’s worth a slow, “leisurely” read. You’ve been warned!]

Leisure, it must be remembered, is not a Sunday afternoon idyll, but the preserve of freedom, of education and culture, and of that undiminished humanity which views the world as a whole. -Josef Pieper

Taken at face value, leisure and slow living seem to be two sides of the same coin, but they’re rooted in very different things.

The “slow living” lifestyle is a mainstream movement rooted in secular culture, although its principles have been adapted by many people of faith -myself included!

Leisure, however, is different. At least, according to Josef Pieper in his essay “Leisure: The Basis of Culture.” Spoiler: Pieper writes that leisure, at its most authentic core, is rooted in divine worship.

In fact, his essay was so profoundly moving the first time I read it that it partially inspired the creation of Radicalis. As my routines were forced to slow down (read: husband deployed), I sought to clarify the relationship between slow living and faith, and I found a beautiful marriage of the two in Pieper’s explanation of true leisure.

If you’ve never attempted a philosophical read before (I hadn’t), I encourage you to be captivated by “Leisure: The Basis of Culture.” In my edition, it was only 50 pages long. And even if some passages are difficult to follow, the general message will grip your heart and purify what you thought it meant to be truly human, with a soul that touches the supernatural, trapped in a world that values an existence of “total work” and rejects the necessity of a Sabbath.

At least, that’s my take.

Radicalis wouldn’t actually be complete without a post on the wisdom shared in Pieper’s “Leisure,” and I hope I do him some slight justice in sharing the wisdom I’ve annotated to death in its pages.

Leisure is education is leisure

So where does this modern philosopher start? With the etymology of some important words. And like many words in the English language (“radical” being one of them), “leisure” has surprising origins.

Leisure in ancient Greek is σχολή (I copied and pasted that), or “skole.” This is an origin of the Latin word “scola,” which is the origin of the English “school.”

Yes, the origin of our modern “school,” is actually “leisure.”

Apart from the implications of what the original purpose of formal education was meant to be, and how far we may have strayed from it, this knowledge also demands a reassessment and reexamining of what we think “leisure” actually is.

In fact, the word in ancient Greek for “work” is “ascholia,” or the negative of their word for “leisure.” In other words, the closest word they had for “work” was “unleisurely,” or the absence of leisure.

We think of leisure as the absence of work. Ancient Greeks thought of work as the absence of leisure. It’s a subtle but profoundly different frame of mind.

Of course, these were ancient pagans before the time of Christ. So how could their ideas of leisure and education inform the modern Christian mind?

Do you try to possess beauty?

Turns out, the ties between Aristotle and the early saints are strong. How Aristotle thought of leisure is very close to how someone like St. Thomas Aquinas would describe Christian contemplation or, most especially, the contemplative life.

But what is contemplation? It’s something effortless, something receptive, and something very leisurely. In other words, it is the antithesis of productive “work.” Pieper says it better:

To contemplate, on the other hand, to ‘look’ in this sense, means to open one’s eyes receptively to whatever offers itself to one’s vision, and the things seen enter into us, so to speak, without calling for any effort or any strain on our part to possess them. (emphasis mine)

When does *enjoying beauty* stop being leisurely contemplation and become something distorted? When we see beauty and immediately begin scheming to possess it, instead of simply contemplating it and receiving it as a gift.

Like looking for a beautiful sunset to take a picture of it for your next social media post, the caption already brewing in your mind. Is this inherently wrong? No. But does it allow you to simply contemplate and receive the beauty of that sunset? I’d argue, no. The sunset has suddenly become utilitarian, a means to a useful end.

Or when we see beauty and feel the need to possess it intellectually. We begin measuring, poking, dissecting, counting, and creating data points.

This isn’t to knock the processes of science. Rather, it’s to show another, essential side of the human experience. Science is work, and a good work. But if we only value the work of science, and never stop to contemplate and receive higher beauty and truth as a gift, as something effortless, then we slowly become less human.

Less leisure is less human

Without practicing true leisure and only valuing work, we slowly become less and less human, and more a fleshy machine that is productive. We know nothing of gifts and only of what we’ve earned on our own power. We live as if we have no soul, because a soul demands beauty and leisure, and there is no practical use in that. We live as if there is only the natural, observable world, and there is no such thing as the supernatural, or the invisible spiritual realm.

As a Christian, our salvation actually stems from our ability to experience leisure, because it is the ability to allow our soul to perceive and receive God. It’s the ability to be okay with accepting God as a gift, and not Someone’s affection we work to earn.

In that vein, I’d say true leisure also demands humility. It’s humbling to admit that although we can work and research until the day we die, there are certain truths that we cannot attain by grasping on our own power. There are certain truths that material science cannot touch.

There are some things meant to be received from a quiet disposition of the soul. And even if you aren’t a scientist, this is convicting. Because allowing time for this quiet disposition is not a high priority for the average human.

Is leisure a waste of time?

So in a way, does this mean leisure is actually more like work, if practicing it can be so hard to do?

No, not by the definition of “work” as “productivity” and something “useful.” Yes, leisure may be difficult because it is a virtue to be learned over time, but the essence of true leisure is effortless and receptive. Nothing could be less useful or productive than something effortless and receptive.

Well then, if leisure is not productive, not materially useful, effortless, receptive, and humbling, then what is the point at all?

There is only a point if it’s rooted in something real.

If leisure is what allows our soul to be open to higher truths and the supernatural, then the supernatural —God— has to be real. I don’t mean this as a blind statement, but to emphasize that there is no point to leisure or contemplation if there is no supernatural, no God. And beauty? That becomes a mere distraction from more important things.

If there is no God or spiritual realm, then there is nothing in leisure to be received as a gift, because there is no Gift Giver. If leisure is really spiritual contemplation, or dare I say, prayer, there has to be Someone to pray to. If leisure is the acknowledgment of your own soul, then the supernatural reality of your soul has to be real.

Otherwise, you might as well go back to work and work to death, because if you’re not useful, you’re pointless and a slowly deteriorating bag of bones.

Goodness is not measured by hard work

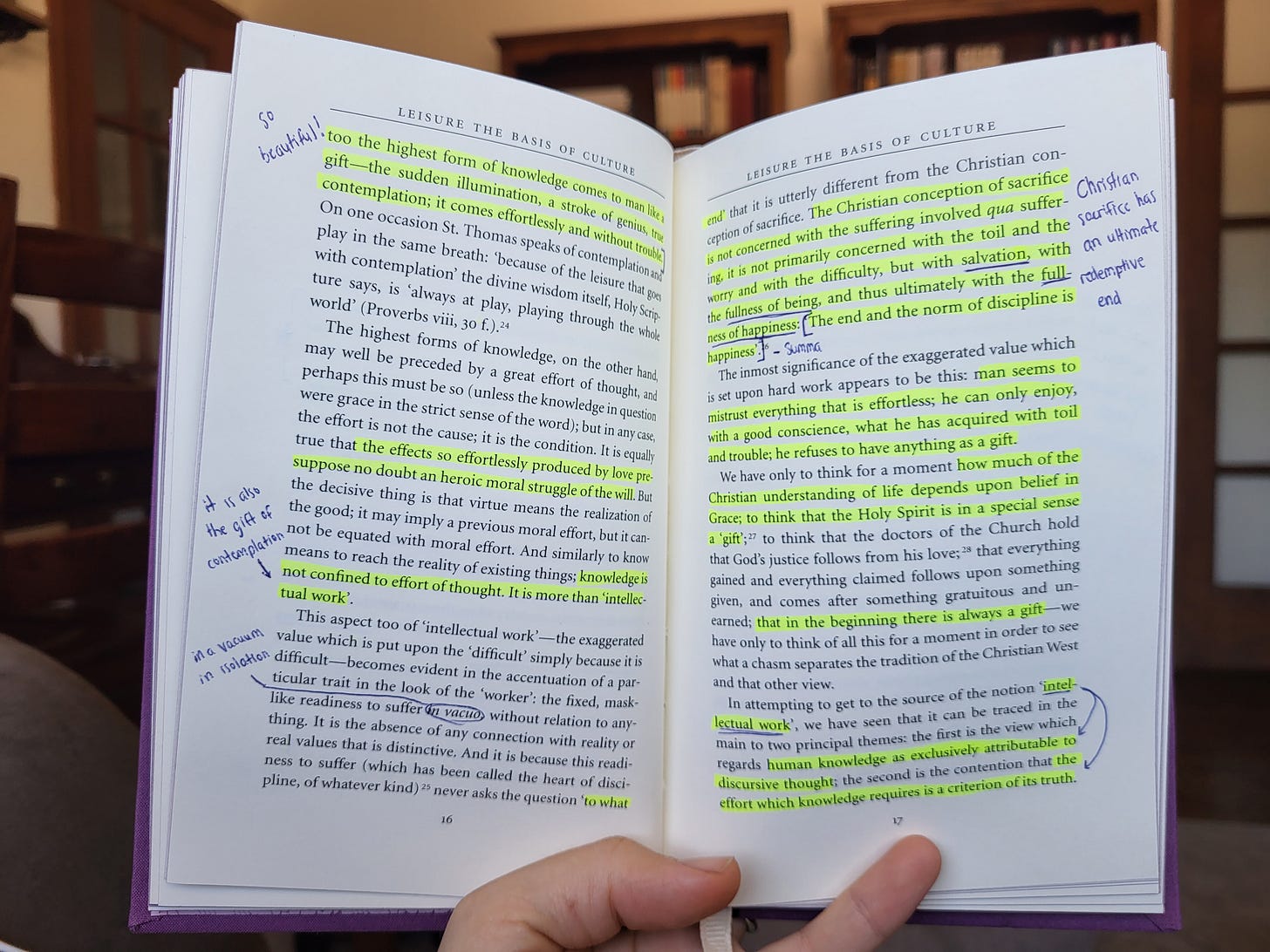

Now that I’ve said too much, let’s get back to Pieper’s own words, because he has some stellar insights to give.

The dehumanizing world of “total work” can even trickle down into some ideas about Christianity. Especially when it comes to virtue and love. How many times has this idea, in one form or another, seemed like a “Christian” point of view:

The more difficult a thing, the higher it is in the order of goodness.

The harder you work for something, the better it is. In other words, leisure, which is effortless, is at the bottom of the order of goodness. In other words, leisure is bad.

Here’s where it gets difficult and nuanced. Because working very hard for something is usually very good. It creates discipline, and discipline is what creates habits of virtue. And let’s be honest, creating any habit of virtue is hard. So why the hate on hard work?

I have no hate for hard work (quite the contrary), but I have come to think that “goodness” is better measured by love than by difficulty.

It’s easier to understand when you examine the progression of the spiritual life and virtue. I’m no expert on that, so I’ll call in Aquinas:

The essence of virtue consists in the good rather than in the difficult.

And what Pieper explains:

The highest moral good is characterized by effortlessness -because it springs from love.

Good that has become effortless springs from love.

Anyway, back to Aquinas with this mic drop:

…the perfection of love wipes out the difficulty. And therefore, if love were to be so perfect that the difficulty vanished altogether, it would be more meritorious still. (emphasis mine)

Maybe we think that “loving thy enemy” is the highest good, because it seems like the hardest thing we could ever do. And yet, love in its purest, most perfected form would make loving our enemies effortless. A final grace and gift from God.

After all, Aquinas reminds us that

The end and the norm of discipline is happiness.

Yes, happiness. Although long-suffering may be involved, the end of the hard work of discipline is not the suffering itself, but Eternal Joy.

Tying this notion of virtue and love back to leisure, Pieper says:

...just as the highest form of virtue knows nothing of difficulty, so too the highest form of knowledge (in leisure) comes to man like a gift -the sudden illumination, a stroke of genius, true contemplation; it comes effortlessly and without trouble.

The more you practice a virtue, the easier it becomes. The more you practice leisure, the more effortless it becomes. Difficulty no longer is a moral measurement of goodness. Instead, love becomes the measurement of goodness (see header of this section).

A religion of “total work” would have you believe that the harder you work and toil, the more “good” you are. It would make leisure a sin. And the infant, child, elderly, and disabled worthless.

The necessity of leisure to the human existence, effortless and rooted in something real and supernatural, defies the idea that for something to be good it must be difficult.

Because in the end, the work itself was part of the journey. Maybe it took grueling hard work for virtue and love to become effortless, and that work still means something. It was the means to that all-important other end: LOVE.

So hard work doesn’t matter?

These pretty words are all well good, until you stare into a life that requires work to live and eat and shelter your loved ones. In real life, hard work matters so much, it’s a means of survival. And there is joy in hard work. There is goodness created in hard work. The punishment given to Adam himself in the Garden of Eden means that if you are human, hard work is unavoidable. And for women, it manifests itself in another feminine way: the “labor” of childbirth.

Goodness cannot be measured by work, but work can be good.

Here is a concept of two things being true simultaneously: to be human is to work hard AND to have leisure.

Of the two, leisure is the higher form of the human experience. And the graces of leisure should trickle into our work. But instead we let work trickle into our leisure.

To beat a dead horse: “work for work’s sake” is not good. And if you are a Christian, we believe (contrary to some popular opinions) that the closely related “suffering for suffering’s sake” is not good. Suffering must become sacrifice, our sacrifice must be redeemed, and that redemption must change us somehow. Some would say we must die many little deaths and “rise again” into something (someone) new.

But where does this tie into leisure?

The highest form of leisure includes sacrifice, because the highest form of leisure, as already implied, is rooted in divine worship. And there is no worship without sacrifice; just look at any religion in history.

No such thing as a feast without Gods

This brings us to a final (whew!) fascinating facet of leisure, which Pieper calls “contemplative celebration.” In other words: feast days and holidays (holy-days).

Feast days and holy-days are the inner source of leisure. It is because leisure takes its origin from ‘celebration’ that it is not only effortless but the direct contrary of effort.

Here we come full circle and draw closest to why leisure is rooted in divine worship. We find it is not only effortless, receptive, and contemplative, but also celebratory!

There is no such thing as a feast ‘without Gods’ —whether it be a carnival or a marriage. There is no such thing as a feast that does not ultimately derive its life from divine worship.

Throughout history, “there [has been] no such thing as a feast without Gods.” And these feasts are only possible when time and space —a Sabbath day and a Temple— are set aside and “transferred to the ‘exclusive property of the Gods,’” as Pieper says.

This time and this space are not useful. They are not productive or utilitarian. They are something much, much more necessary to human existence than that. It is the leisure to worship and feed our souls in ways that allow us to surpass worldly work and remember our ultimate purpose and destination.

In fact, Pieper would argue, as his title suggests, that leisure is the basis of culture. Because there is no culture that is not rooted in worship of some kind, for better or for worse.

Without worship, culture and leisure and arts and education and freedom and a higher sphere of human existence do not exist (see opening quote to this article). Without worship, the “spiritually impoverished” grasp for something to idolize, and the world of “total work” becomes their religion.

And this world is “a poor, impoverished world, be it ever so rich in material goods.” In contrast

divine worship, of its very nature, creates a sphere of real wealth and superfluity, even in the midst of the direst material want —because sacrifice is the living heart of worship…a free offering freely given and never anything useful or utilitarian…in the sacrifice of the cultus a capital wealth is created which the world of work can never consume.

We are an Easter people

By this definition, the neglect of leisure could be seen as a sin against the commandment: “remember to keep holy the Lord’s day.” And Sabbath rest becomes not only something that reflects the dignity of our natural+supernatural humanity, but a moral obligation.

Throughout his entire essay, Pieper has explored leisure through the lens of Christian worship, but in the final two pages he says it explicitly:

post Christum (after Christ), there is only one, true and final form of celebrating divine worship, the sacramental sacrifice of the Christian Church…the Christian cultus, unlike any other, is at once a sacrifice and a sacrament.

No one is more leisurely than the Christian.

And the highest form of leisure on earth is the liturgy of the Mass and the sacraments, and following the liturgical calendar of the Church, which provides us with countless feasts, holy-days, and traditions to celebrate in festive companionship with the communion of saints and our God.

“We are an Easter people, and Alleluia is our song!” -St. John Paul the Great

This is where we too will leave off in our discussion. With the conviction that leisure is not just a fun way to enjoy “free time” between work, but that it is a human necessity and a foundation of a truly free, Christian culture.

The simple question then becomes much more profound:

How do you spend your leisure?

If you made it this far

You can look forward to a much less intellectual —and shorter— next post, just to keep things balanced.

Thank you for exploring this topic which has spoken so deeply to me, and I hope it speaks to you as well. Pieper has a lot more wisdom to share in his essay: “Leisure: The Basis of Culture,” so check it out for yourself.

Drop me a comment or a reply and let me know if anything touched you in particular while you were reading!

Other notable quotes from Pieper’s “Leisure:”

…that we may be rapt into love of the invisible reality through the visibility of that first and ultimate sacrament: the Incarnation.

There is also a certain happiness in leisure, something of the happiness that comes from the recognition of the mysteriousness of the universe and the recognition of our incapacity to understand it, that comes with a deep confidence.

No one who looks to leisure to restore his working powers will ever discover the fruit of leisure.

In its extreme form the passion for work, naturally blind to ever form of divine worship and often inimical to it, turns abruptly into its contrary, and work becomes a cult, becomes a religion.

One can only be bored if the spiritual power to enjoy leisure, or if you prefer, to be leisurely, has died away.

Some visual beauty to share…

Take a moment to enjoy some beauty and discussion of “slow living” with this 8-minute video on a minimalist’s month-long trip to Italy and the culture’s slower pace of life. And now I wish Americans had a daily “siesta” as well!

I’m new to your site- found you through Meredith’s page- and I just loved this. Thank you for spurring on my heart to the beauty of worship and thinking about leisure in a new way!!! I feel smarter by reading this, too ;).

Great article! Putting this into words really spoke to me, especially with the way our culture is headed. 😔

>>>>>A religion of “total work” would have you believe that the harder you work and toil, the more “good” you are. It would make leisure a sin. And the infant, child, elderly, and disabled worthless.<<<<<